在我進小學之前,我的世界只有一種語言 — 客家話。

那是一種夾雜咒罵與催促的話語,粗粝中帶有很多情緒的刮痕。家裡的大人話說得不多,有也只是用來命令、責罵、或抱怨,我找不到柔軟的詞語可以安放我年幼的心。家裡唯一看得到像書的東西,是廟裡拿回來的農民曆。

這個語言裡沒有故事,沒有安慰,也沒有溫柔的催眠曲。在我幼年的耳朵裡,語言是不悅耳的噪音,是成人怒氣與勞動的副產品。我不知道語言還能有別的樣子,直到六歲那年走進學校的那一天。那是我生命中第一次看到書 — 真正意義上的「書」。

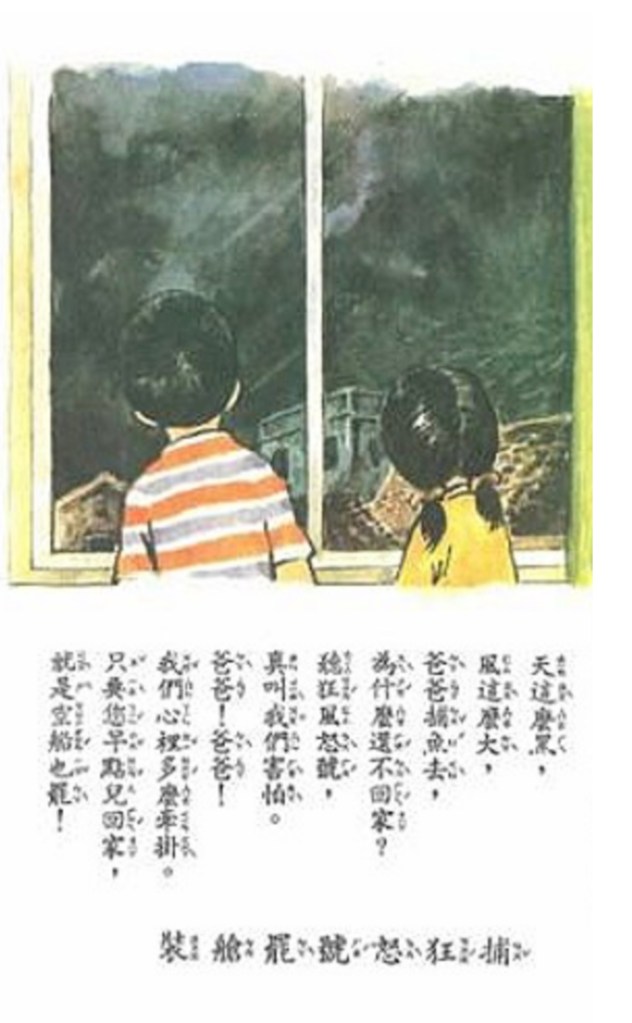

它是國語課本,乾淨無皺褶的紙張上印著黑色正體的文字,上面有漂亮的彩繪插圖。老師用一種我從沒聽過的聲音,讀著那上面的句子:「天這麼黑,風這麼大,爸爸捕魚去,為什麼還不回家?」

我聽呆了。原來,字可以連成一句句如此有畫面的話,平穩、簡潔、又富有節奏。我不知道,語言竟然可以不吵、不怒,而是慢慢地、安靜地勾勒出我沒見過的影像。

The day I first saw words,

I sat frozen in wonder.

Words could join together to form images,

flowing with rhythm, simple and serene.

I never knew language could be quiet,

unhurried,

unburdened by rage.

A voice that gently drew pictures

I had never seen before.

These Mandarin lines

were like wind gliding over water,

like moonlight spilling into dreams.

Each word stirred ripples across the lake of my heart.

那是我第一次認識「中文」,它不屬於家裡,也不屬於我,但,我想要學習它。

然而,沒上過幼稚園的我,什麼都不會,連注音符號都認不出來。作文課上,我常常一段話都寫不出來。不是我不想寫,而是我的世界太小,詞彙太少,會寫的字少得可憐。我…. 說不出話來。

但我渴望知道更多。上學,是我每天最期待的事,因為我知道,老師會說出新的詞,黑板會出現新的字,課本會翻到下一張嶄新的世界。那時候的我,像一棵在沙漠裡等待雨水的小草,貪婪地吸收能接觸到的每一滴字句。

漸漸地,我背起了唐詩,學起了宋詞,開始記得「舉頭望明月,低頭思故鄉」的節奏,懂得「采菊東籬下,悠然見南山」的寧靜。這些詞句不像客家話聽起來那樣粗糙,它們像風吹過水面,像月光照進夢裡,每個字句都在心湖上泛起漣漪。

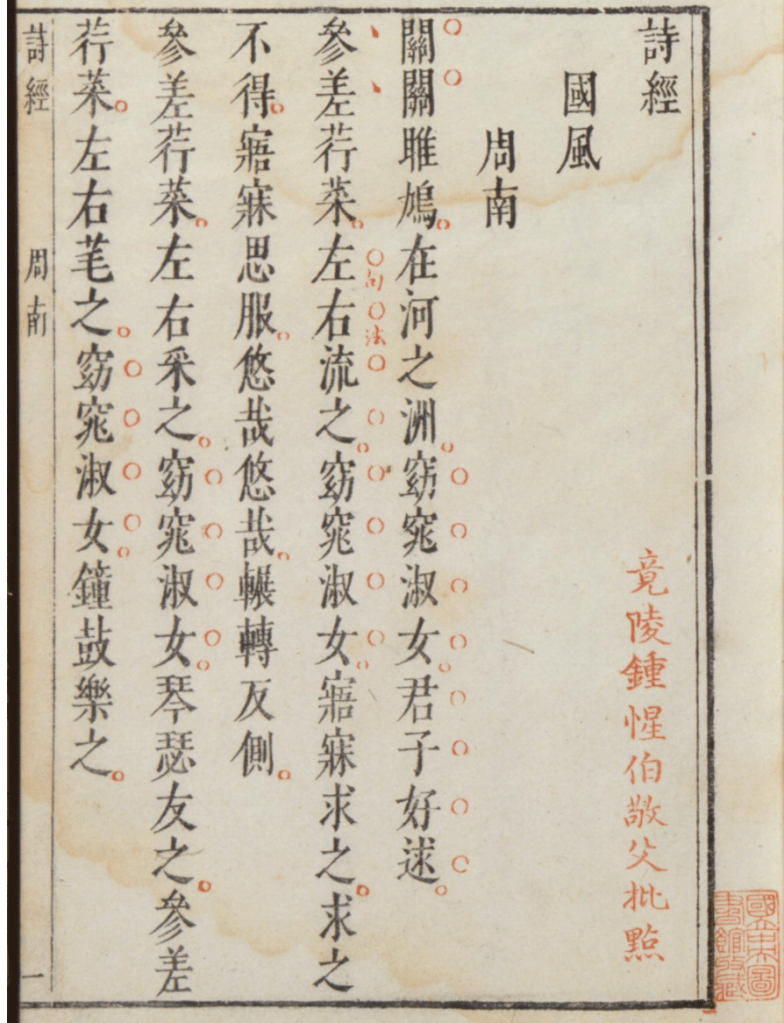

國中以後,開始接觸《論語》《詩經》《資治通鑑》,才明白中文不只是詩句優美,它還可以深沉似江海,廣博勝百嶽。每個字都有靈魂,藏著古人對人生的回應、對天下的感悟。我逐漸感受到中文不只是一個語言,它是一種存在的方式。它像一把鑰匙,打開了我靈魂深處那扇想說話、想被理解、也想認識世界的大門。

中文的美,很多是翻譯不來的。漢字裏的「靜」與「慢」,「隱」與「讓」,那種深藏不露、含蓄飽滿的情感,只能在字的縱橫筆劃中被捕捉。這種語言,是千百個靈魂在時間長河中留下的足跡。

如今的我,無比慶幸自己被中文孕育,從農民曆到《詩經》,從客家話到宋詞,它一路牽著我走過混沌與迷惘。哪怕我曾經什麼都不會,哪怕我曾是那個作文課一個字都寫不出來的孩子。正因為曾經如此匱乏,我才更懂得,語言是如何照亮了我,我又該如何用它說話。

六歲那一年,我看見字的樣子。

也是那一天,我看見了一個渴望說話的靈魂,在我體內睜開了眼。

The year was 1985, in a farming village in Taiwan where life moved with the seasons. Women carried baskets of clothes to the riverbank, squatting on the rocks as they beat fabric clean with wooden paddles. By dusk, those same paddles would often vanish into children’s hands, repurposed into makeshift baseball bats as they played under the fading light.

Most families kept chickens or ducks scratching in the yard, and planted vegetables in narrow strips of soil by the fields. The harvest was small but steady, enough to season the daily meals. Laughter and smoke from roasting sweet potatoes often drifted through the lanes.

My family was the poorest household in the village. My mother, unable to read or write, bore the weight of raising two children and caring for her aging parents alone. My brother and I were among the only child laborers; while other children chased balls across the rice fields, we rose before dawn to assemble Christmas lights for pay.

Before I entered elementary school, my world held only one language — Hakka. It was a tongue woven with scolding and urgency, words rasping with the rough edges of emotion.

“Ayïma, bring slipper here!”

“Pork not yours, Ayïma. Take porridge!”

Ayïma was the hakka name my grandparents called me. The adults at home rarely spoke to me, and when they did, it was to command, to criticize, to complain. Nowhere in their voices could I find a gentle word to shelter my small, tender heart.

In Hakka, there were no stories, no lullabies, no words of comfort. To my young ears, language was nothing more than harsh noise — the byproduct of anger and endless labor.

I did not know language could take another shape, until the day I was six years old and walked into school for the first time. That was the day I encountered a book — a real book.

It was the Mandarin textbook, its clean pages uncreased, the black characters marching neatly across the paper, accompanied by bright, colorful illustrations. The teacher read aloud in a voice unlike any I had ever heard:

“The sky is so dark,

the wind so strong.

Father has gone to fish.

Why hasn’t he come home?”

I sat frozen in wonder. Words could join together to form images, flowing with rhythm, simple and serene. I never knew language could be quiet, unhurried, unburdened by rage. A voice that gently drew pictures I had never seen before. That was the first time I encountered Mandarin.

It did not belong to my home, nor to me — yet I longed to learn it.

I had never gone to kindergarten, never learned the basic phonetic symbols. I knew nothing at all. During composition class, I often sat before a blank page, unable to write a single sentence. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to write — it was that my world was too small, my vocabulary too meager, the Chinese characters I could use too pitifully few.

I… had no words.

And yet, I hungered for more. School became the thing I looked forward to each day, because I knew the teacher would speak new words, the blackboard would bloom with new characters, and the textbook would open to another untouched world. I was like a blade of grass waiting in the desert for rain, drinking in every drop of language I could reach.

Little by little, I began to memorize Tang Poems and learn the rhythms of Song Verses. I carried in my mouth the cadence of

“I raise my head to the moon’s clear light, Then lower it, longing for home in the night.”

Unlike the rough Hakka tongue that had shaped my earliest years, these Mandarin lines were like wind gliding over water, like moonlight spilling into dreams. Each word stirred ripples across the lake of my heart.

Language was no longer noise. It had become a key — one I longed, with all my small and stubborn mind, to hold.

Six years old — that was the year I first saw the shape of words.

And for the first time, I saw the soul inside me, longing to speak.