Prologue

I was once a child whose world began in silence.

Not the gentle silence of peace, but the kind carved by hunger, by labor, by the weight of things too heavy for small hands to carry.

There were mornings when I rose before the sun, and nights when I stitched myself into exhaustion, still believing that tomorrow might open its palm and spare me a drop of kindness.

I learned early that life would not hand me a seat at the table. If I wanted a place, I would have to carve one. So I became the girl who bent but did not break, who turned scraps into shelter, and emptiness into resolve.

Through the years, there were moments — fleeting, fragile —

when a hand reached out,

when a smile cracked open the darkness,

when a kindness felt like rain after a long drought.

Those moments kept me alive. They taught me that even the smallest flame, once lit, can defy the night.

This book is not a tale of victory, but of endurance. It is not about becoming someone extraordinary, but about daring to walk forward when the ground keeps collapsing beneath your feet.

I write because silence has a way of swallowing us whole, and I want to leave behind proof — that even in the harshest soil, something can still grow.

This is the voice of the girl I once was, and the woman I have become. If you, too, have carried your life in bruised hands, may you find in these pages a mirror, a breath, a quiet reminder that you are not alone.

Chapter 1 The Day I First Saw Words

The year was 1985, in a farming village in Taiwan where life moved with the seasons. Women carried baskets of clothes to the riverbank, squatting on the rocks as they beat fabric clean with wooden paddles. By dusk, those same paddles would often vanish into children’s hands, repurposed into makeshift baseball bats as they played under the fading light.

Most families kept chickens or ducks scratching in the yard, and planted vegetables in narrow strips of soil by the fields or in patches of fallow rice paddies. The harvest was small but steady, enough to season the daily meals. Laughter and smoke from roasting sweet potatoes often drifted through the lanes.

But my family was different. We were the poorest household in the village. My mother, unable to read or write, bore the weight of raising two children and caring for her aging parents alone. My brother and I were among the only child laborers; while other children chased balls across the rice fields, we rose before dawn to assemble Christmas lights for pay.

Before I entered elementary school, my world held only one language — Hakka. It was a tongue woven with scolding and urgency, words rasping with the rough edges of emotion.

“Ayïma, bring slipper here!”

“Pork not yours, Ayïma. Take porridge!”

Ayïma was the hakka name my grandparents called me. The adults at home rarely spoke to me, and when they did, it was to command, to criticize, to complain. Nowhere in their voices could I find a gentle word to shelter my small, tender heart.

In that language, there were no stories, no lullabies, no words of comfort. To my young ears, language was nothing more than harsh noise — the byproduct of anger and endless labor.

I did not know language could take another shape, until the day I was six years old and walked into school for the first time. That was the day I encountered a book — a real book.

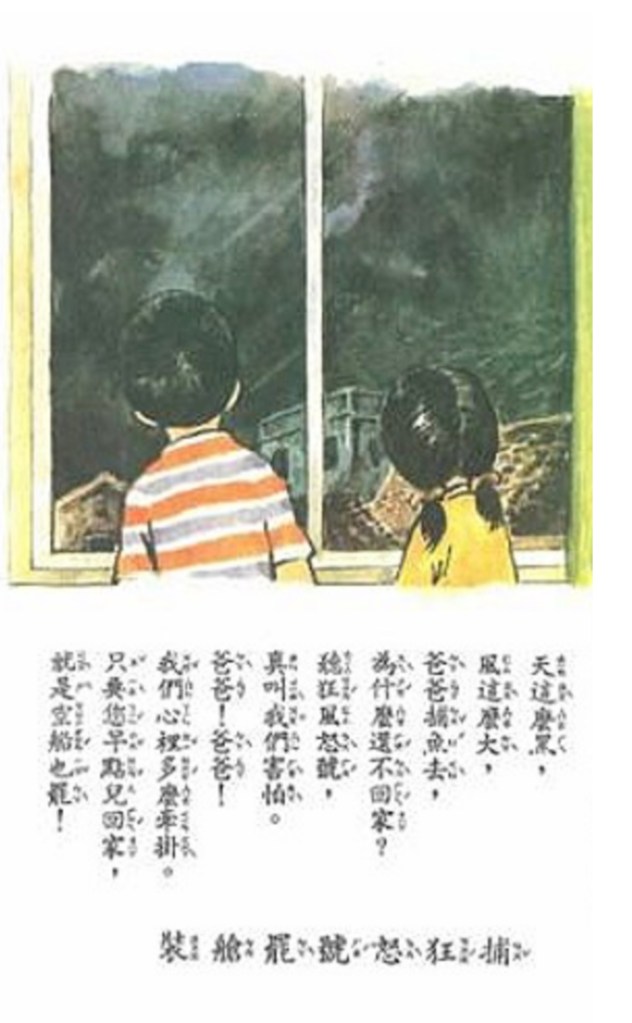

It was the Mandarin textbook, its clean pages uncreased, the black characters marching neatly across the paper, accompanied by bright, colorful illustrations. The teacher read aloud in a voice unlike any I had ever heard:

“The sky is so dark,

the wind so strong.

Father has gone to fish.

Why hasn’t he come home?”

I sat frozen in wonder. Words could join together to form images, flowing with rhythm, simple and serene. I never knew language could be quiet, unhurried, unburdened by rage. A voice that gently drew pictures I had never seen before. That was the first time I encountered Mandarin.

It did not belong to my home, nor to me — yet I longed to learn it.

But I had never gone to kindergarten. I knew nothing at all. I couldn’t even recognize the phonetic symbols. During composition class, I often sat before a blank page, unable to write a single sentence. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to write — it was that my world was too small, my vocabulary too meager, the Chinese characters I could use too pitifully few… I… had no words.

And yet, I hungered for more. School became the thing I looked forward to each day, because I knew the teacher would speak new words, the blackboard would bloom with new characters, and the textbook would open to another untouched world. I was like a blade of grass waiting in the desert for rain, drinking in every drop of language I could reach.

Little by little, I began to memorize Tang Poems and learn the rhythms of Song Verses. I carried in my mouth the cadence of

“I raise my head to the moon’s clear light, Then lower it, longing for home in the night.”

I absorbed the stillness of

“Plucking chrysanthemums by the eastern wall,

Serenely glimpsing the southern mountain tall.”

Unlike the rough Hakka tongue that had shaped my preschool years, these Mandarin lines were like wind gliding over water, like moonlight spilling into dreams. Each word stirred ripples across the lake of my heart.

Language was no longer noise. It had become a key — one I longed, with all my small and stubborn mind, to hold.

Six years old — that was the year I first saw the shape of words.

And for the first time, I saw the soul inside me, longing to speak.

But outside the classroom, silence wore another name. It was not wonder — it was shame. And soon, the words I carried home were not poems, but labels others carved onto my skin.

Chapter 2 Dignity or Dinner

“There she is again, that beggar!”

A few classmates stood nearby, making sure their voices were loud enough for me to hear.

I kept my head down, pretending not to notice. I stood by the iron barrels where the classmates dumped the leftovers. With trembling hands, I scooped rice into a plastic bag I’d brought from home. The room filled with the sound of laughter — sharp, merciless, like stones thrown at my back. Everyone knew what it meant: I was the girl who collected what others discarded.

Quickly and carefully, I gathered all the rice, trying not to waste a single grain. I tied the bag up neatly, and tucked it beneath my seat to take home after school. In my mind, I was already calculating: in a few weeks, the chickens at home would be ready to butcher. Maybe this time, I could ask for a drumstick.

“Ayïma, the meat’s too tough to swallow for a girl. Just eat the skin,” the grown-ups always said.

I was small, they claimed, too young to chew through meat. Fat and skin were more suitable for girls like me. The tasty drumsticks always landed in my brother’s bowl. My portion was the skin stripped off chicken flesh. Most of the time, my food was the cloudy broth poured over a bowl of rice. No one explained this division. It was the order of things, as natural as sunrise.

Even Old Blackie, the neighbor’s dog, ate better than I did. His bowl carried meat, bones, pork fat and skin, scraps richer than my thin broth.

For as long as I could remember, I’d been alone. Every morning, the only visitor was the sun, peeking through the distant Dongyan Mountains, spilling light into our doorway for a brief moment. My most loyal companion was the Old Blackie himself. We often sat side by side, our eyes following the road where my brother and the other children marched off to kindergarten. Old Blackie never spoke, but his silence felt less cruel than the world’s.

“Worthless girl!”

That was the label my grandfather slapped on me the day I was born.

“A mouth to feed and useless! Throw her out! See if anyone wants her!!” Grandfather had shouted, bound by the beliefs of an older Chinese era.

In our rural village, the rules were older than any of us. Boys carried the family name; girls carried only the weight of being someone else’s daughter-in-law one day. A boy was a seed for the future, a girl — an expense.

“She’s mine. I birthed her, I’ll keep her. I don’t care what you say. You can’t throw her out!!” my mother replied firmly, refusing to let go.

So the worthless girl stayed. And Mother was chained, from that moment on, to endless work.

“When can I be a boy?” I used to ask my mom, wide-eyed and hopeful.

I wanted to be a boy. Boys just had to frown to be pulled into someone’s arms. They ate whatever they wanted — no one said, “That’s too tough for you.”

“What you are’s what you are,” Mother would say softly. “You just take what you’re given.”

Even as a child, I understood my fate was like a stray dog’s. But I swore — if I had to be a dog, I’d be a good one. I’d be a useful guard dog.

So I began to overachieve. I brought Grandpa his cigarettes, brewed tea, fetched his slippers. I swept the floor, washed vegetables, did laundry for Grandma. I learned to sew to please my mother, and took plastic bags to school to ask for leftovers.

Soon, more labels stuck to me, sharp as burrs on bare skin:

“Bastard”

“Freak”

“Beggar”

They weren’t whispered — they were branded, loud and hot, pressed onto my skin like burning irons. And when I tried to peel them off, alone in some corners, the glue had already seeped too deep. My skin tore. The words stayed.

The thirty-minute walk home always felt too long — my fingers ached from carrying the bag of rice. But it also felt short — too short for me to swallow down the shame before reaching our door.

I often asked myself: dignity or dinner? I always had to choose the latter. Because dignity had never been offered to me. And hunger was something only I could quiet.

But maybe because my face was always covered with labels, I began to notice the ones others wore too. When a classmate was scolded for failing a test, I helped with their study if I could. When someone was left out, I sat beside them. Maybe I just wanted the world to be kinder to others — hoping, one day, the world might be kinder to me too.

I gave what I was never given, and in that giving, I secretly rehearsed the shape of dignity.

Hunger made its claim early. But before I even sat in the classroom, I had already learned the sound of the sewing machine — earlier than the laughter of children outside. That was how my childhood began: not with toys, but with work.

And yet, when I dragged my aching fingers home with the bag of rice, Old Blackie was always there by the door. He wagged his tail as if nothing about me was shameful, as if surviving was enough. In his warm gaze, I felt the only welcome the world knew how to give.

Soul Whisper :

When others slap labels on you, it’s to define you, to diminish you, to keep your head down. But you don’t have to follow their script. You lower your head only to see the road more clearly. You gather every grain of rice, and with it, your dignity.

Don’t let those words be your ending. You turned them into soil to let the labels grow roots — and from those roots, a spine, feathers, and finally, wings. Even if you were born in barren ground. Even if others called you useless, unworthy, forgettable — you turned every insult into lift.

So if you’re walking through darkness, remember this:

You are not the names they called you.

You are who you’ve fought to become.

You are the wing still forming beneath the label.

So don’t rip it off too quickly. It may be the very thing that’s about to carry you over the wall you thought you’d never climb.

Chapter 3 Open Window

Before I began school, Mother worked from home, stitching judo kimonos for a factory. In Taiwan then, there were no public kindergartens — every one was private and costly. Because I was the worthless girl, no one thought it worth the money to send me to kindergarten. So I stayed home, watching Mother work.

With my little eyes, I studied how she threaded the needle, pressed the foot pedal, aligned the cloth. I learned by watching, quietly, carefully.

Once I started elementary school, Mother went to work at the factory. After school, I tried the sewing machine, out of curiosity, and out of a desperate need to prove I was useful. I wanted to be a good dog. A guard dog they wouldn’t throw away.

Surprisingly, my work passed factory inspection. I could earn money. At six, I became a worker.

The sewing machine felt like a magical toy — sleek and powerful, something no other kids could touch. No one in the village had ever seen a child my age operating an industrial sewing machine. They came to watch, whispering, amazed. If we’d had smartphones back then, I’d have gone viral. But what started as pride quickly became pressure. Because once you can make money, it’s no longer a game.

My mother began setting daily quotas. If I didn’t finish, there would be bamboo stick punishment. When the factory rushed orders, school came second — I stayed home to sew. Gradually, weekends disappeared. Holidays too. Every day of the year, I sewed. Labor filled the hours. Lessons, if any, came after.

What began as play turned into a nightmare. I often wished to wake up from it — but the dream dragged on, all the way through the last year of my middle school. I still remember reciting the ancient Chinese ballad of Mulan — “click-clack goes the loom" — feeling it in my bones.

The sewing room was a tiny, three square meters space. Just two machines and baskets to hold judo kimonos. My machine sat by the weathered red wooden door with peeling paint, beneath a window that faced the road.

I always kept the window open.

Outside were endless rice fields, and beyond them, Dongyan Mountains. It was a quiet, simpler time. After school, the road became the playground.

Kids played badminton in the open lane,

chased each other through make-believe games.

With “red light, green light!” — freeze, then dash,

muddy heels in a wildgrass flash.

After harvest, they'd take the rice field —

turn stubbled ground to a baseball shield.

When the sky turned gold,

they lit small fires, let stories unfold.

Sweet potatoes charred in smoky rings,

and malt sugar stuck to dirty hands like dreams.

Even in winter, I left the window open.

While my hands stitched fabric, my mind wandered outside. I listened to the kids’ laughter, their swear when sweet potatoes burned.

They laughed, and I laughed too.

They cursed, and I echoed a word or two.

As if I were standing by the fire’s glow,

On the ridge where the warm winds blow.

As if I had tasted, on my tongue,

that scorched malt sugar the children sung.

What was a happy childhood?

Things I glimpsed through that window — barefoot baseball in the meadow, chasing crickets in fields of gold, faces smeared with dust and laughter bold. Was this the shape of a carefree childhood? Or was it meals and music, brush and board — a life where every path was yours to afford?

For me, it was only a tale told from afar — A glimmering vision through the window’s bar.

As the “unwanted girl" of a single-parent home, I had real worries: Could I pay for next month’s lunch? When would I have time to do homework? Would I be beaten again if I fail to fulfill my work quota? Could I go to school tomorrow?

My days unspooled like a black-and-white reel of exhaustion and ache, as I sewed from dusk till dawn. But… I always kept that window open.

Soul Whisper:

In all the hardship, I kept my window open. Through that narrow frame, I saw a world I didn’t yet belong to, but longed for — a world full of light and freedom.

I was then just a little girl bent over a judo kimono, but that sewing skill — the very thing that once tormented me — would later become the backbone of my survival. Looking back, I see that what I thought would break me, built me instead. The sewing machine chained my hands, but I had the heart of someone reaching for the stars.

So if you’re standing in a small room, your back aching, your life threadbare — leave your window open. Let the wind carry your dreams farther than your feet can go. What you see outside may not be yours yet, but it can become yours.

Let the world whisper back.

Chapter 4 The Tears of Faucets

“Go wait in the hallway. Don’t stay in the classroom and disturb the others while they eat,” Ms Tsai said in front of everyone.

Ms Tsai, our homeroom teacher, was an elderly woman, close to retirement age — the kind of strict, old-fashioned teacher who believed discipline was the only true education. To her, order mattered more than hunger. Rules were rules, and pity was weakness.

Our elementary school had more than three thousand students. A city within a city. Rows of identical classrooms, each one filled to the brim. Each classroom opened to the hallway, where a row of faucets lined the wall — ten to a class, endless down the corridor.

Everything was fixed: the classrooms never changed, and every student had a seat that stayed the same the whole year. That desk was our little island, where we studied, doodled, and at noon, turned it into a dining table.

The school had a central kitchen that cooked fresh meals every morning. At lunchtime, steaming pots of rice, barrels of meat with vegetables and soup were delivered to each classroom. The smell spread through the hallways long before the bell rang, making every stomach twist with anticipation. Children lined up with their metal trays, waiting their turn, before carrying their lunch back to their seats. It was always hot, always balanced — rice or noodles, three side dishes, and soup.

A small luxury every child could count on.

Every child, except me.

Because I didn’t pay the lunch fee, I wasn’t allowed to join the line, nor sit at my desk with the others. The rule was simple and merciless: “If you didn’t pay, you don’t eat.” And Ms Tsai made sure of it. Every single day.

The moment the food carts rattled into the room, her eyes would sweep toward me. Then came the sentence I dreaded most: “Go wait in the hallway.”

A ripple of giggles always followed, light and cruel. My face burned as I stepped outside, the classroom door clicking shut behind me.

From the very first week of first grade, I had been labeled troublemaker. Not because I misbehaved — but because I was poor. I had never gone to kindergarten. I didn’t know any of the Chinese phonetic symbols. I never had money for lunch fees, never brought a single coin for field trips or class donations. Anything with a price tag excluded me. And in the teacher’s eyes, exclusion meant defect.

But I loved school. To me, the campus was a paradise: swings soared like wings, slides polished by a hundred joyous descents, and the soft fabric of the navy pleated skirt brushed against my knees.

For the first time in my life, I had something that was mine alone — a uniform with my name stitched in clean characters. I wore it with reverence. Because with it, I wasn’t the worthless girl in hand-me-downs. The uniform made me like going to school.

However, not paying lunch fees made lunchtime torture.

Standing outside in the corridor, the smell of curry chicken or orange-pork would seep into every corner of the school. My mouth watered beyond control — a flood I couldn’t hold. My stomach roared like thunder, sharpening knives in the dark below.

Those thirty minutes of lunch felt like a century. Most of the time, I stood by the faucets and watched the water drip, drip, drip… they looked like tears… no one bothered to wipe away…

“Don’t cry. I’m here for you,” I whispered to the faucets.

One day, I was too hungry to bear it. I walked to the second-grade classroom section and found my brother.

“Brother, I’m so hungry. The noodle soup today smells so good…”

That day’s lunch was meat noodle soup and a cupcake.

He led me to the faucets, turned the water on, and said to me, “If you’re hungry, drink it. If you’re still hungry, drink again and more. Fill your belly with water and it won’t hurt anymore. Got it?”

It was his way of teaching me how to survive.

So the faucet’s tears, their sorrow, drop by drop, all flowed into my stomach.

When our first report cards came out, I was ranked second in my class. I got a certificate, a cupcake, and — most shocking of all — praise from Ms Tsai. It was the first time in my life a teacher had ever said something kind to me. I felt school was not pushing me away but drawing me in.

But whether or not I could go to school wasn’t up to me. If the factory had rush orders, I had to “get sick” and stay home to work. The sound of sewing machine filled those days — “click-clack, click-clack” — as I pushed judo kimonos through the machine, riding that iron beast like a soldier riding to war.

At six, I didn’t understand why my mother needed me to work so much. But I wanted to please her as much as I could. Back then, Mother was the only warmth I knew in this world.

Was that love? I wanted it to be …. with every bit of my hungry and trembling heart.

The final term of the first grade I got the best scores of the class. Mother decided to treat Brother and I to something special on her payday. That evening, she took us to the night market. This was a reward not only for my good grades but also for the daily work we did to help ease her burden.

The night market was a wonderland to me. Everywhere I looked, there were lights, colors, and smells that pulled me in all directions. Food stalls sizzled with fried chicken, green onion pancakes, and skewers dripping with sauce. Candy-colored toys and beautiful clothes spun under bright lamps. It was a world far from our plain dinners and worn-out clothes.

Brother and I finally settled on a steaming bowl of vermicelli. We shared it, leaning over the bowl, slurping hungrily until only the last drops of soup were left. I realized Mother didn’t take any bite.

“Mom, you want a bite?” I quickly asked.

“No, no. I’m not hungry. You guys go ahead. Finish it,” she looked at us with a smile.

Mother was not hungry. She was never hungry.

Mother had never been to school. With no education, her hands became her only credentials. She worked as a tea picker in the mountains, sewed clothes for pennies, sold vegetables by the roadside, and cleaned restrooms — whatever work could keep us alive.

She always told us, ”These jobs are filthy work, but the money’s honest. We sweat for every coin. It’s hard, but when we spend it, we don’t owe anyone shame.”

“Our palms should face down, not up,” she would repeat, meaning we must always give rather than ask. That’s why she never walked past a beggar on the street empty-handed, always dropping a few coins into their bowls.

In our household, the number-one principle was making money: every minute of spare time should be used to work. The second was saving it. Nothing was too small to reuse, nothing too broken to repair.

We grew our own vegetables, raised our own chickens, carried cement and bricks with our bare hands to patch up the house. Old clothes from Mother’s coworkers became our wardrobe, discarded fabric scraps from the garment factory were stuffed into cloth covers to make our quilts. We even ate watermelon rinds from neighbors. The list of saving hacks was endless.

Yet, when it came to her parents, Mother never hesitated to spend. She bought them a television so they wouldn’t feel lonely, and a small portable heater so Grandpa wouldn’t freeze through the winter nights.

That evening, after finishing that bowl of vermicelli, we passed a fruit stall gleaming with California plums and nectarines — imported fruits so bright, so colorful, so fragrant, that Brother and I couldn’t help but stare. They looked like treasures from another world.

Mother hesitated, her gaze hovering over the pile of shining fruit. Finally, she picked out two plums — deep purple, their skins polished to a shine as if someone had rubbed them with velvet. She weighted them in her palm as if they were made of gold.

The vendor dropped them into a plastic bag, asked, “Only two?”

Mother gave him a quick smile. She pressed the money into his hand and hurried us away.

When we were a few steps off, she whispered softly: “These are too expensive. We’ve already spent too much today — the bus fare, the noodle, and now this. I couldn’t buy more. These are for Grandpa and Grandma. If they ask, tell them we ate our plums on the way home, alright?”

We nodded. I asked to carry the plums. The sweet fragrance floated up, rich and tempting, made my mouth water.

As we walked from the bus stop to home, the two plums glowing like dark lanterns in the dusk. Their perfume followed us down the dirt road, stronger with each step, so intoxicating. I felt giddy with happiness. We had gone to the night market, eaten oyster vermicelli, and now with this magical fruit in my hand. I wanted to remember the taste of that soup, the smell of the plums, and the pocket of happiness on this night.

“It’s gone……” Mother’s voice cracked with despair.

“My pay envelope… it’s stolen!” she began to cry — loud, broken sobs tearing through the night air.

I froze, unable to move. The joy collapsed inside me. My heart sank with every sob that tore from Mother’s throat. I thought of the three of us, laboring day after day for an entire month, and of the month ahead — how we would survive it now, with nothing left.

I thought of the lunchtime torment that would return to me at school, the smell of food that I could not touch, and the tears of the faucets I had to swallow.

I lifted my head and looked at the sheet of black, merciless and vast sky. My tears slid down silently. Why?! What had we done wrong? Why could we not even have one night of happiness?

People say that suffering builds strength. Can bitterness, if swallowed long enough, turn sweet?

I don’t know, but I sincerely hope so, hoping that somewhere, beyond the sound of dripping, the world is listening. And one day, not every tear will have to be swallowed.

Soul Whisper:

What my mother gave me back then was not comfort, not warmth, not even enough food. What she gave me was something fiercer: the dignity of labor.

She believed that even the poorest hands could hold their heads high if they worked honestly. That filthy hands could still lift a clean heart. It was the shield she handed me — against a world that often takes more than it gives. And I still carry it with me, deep in my heart — the dignity of labor, fierce and unbroken.

Chapter 5 A Day of Light

I stared at a feather-shaped cloud in the sky, head tilted high, eyes wide open. I didn’t dare blink — afraid that the moment I did, my tears would break loose.

We walked down a country road lined with bamboo groves. My mother gripped one bamboo cane, the most common tool for discipline in Taiwan, in her hand and swung as she walked, striking my legs with every few steps.

Pingde Road stretched nearly a kilometer, flanked by scattered groves of bamboo. Each time the cane broke, she snapped off another one within seconds — green, sharp, and fresh. I could tell which ones would sting the most, just by the sound. And even now, those cracks still echo in my ears.

I didn’t know how many canes she broke. I only remembered that the walk home felt endless.

“A-Hsiang, don’t go too far hitting a child like that!” Auntie Chen called out.

“What are you doing, trying to beat her to death?” Uncle Liu from down the lane added.

“She dared to sneak out without permission, of course she gets beaten home!” my mother shouted back, her fury undiminished, her arm still swinging.

It had all started at school earlier that day, when Fen mentioned her Barbies at home. She had gotten two new ones for her birthday, each with beautiful clothes and shiny high heels.

I had never seen a Barbie in my life. In 1980s Taiwan, Barbie dolls were rare treasures, imported and costly, reserved only for wealthy families. To me, it was like hearing about a creature from another world. My curiosity was wild.

“Wanna come to my house after school and play with them?”

“Yes! Yes!” I shouted with joy.

I had never looked forward to anything so much.

Each Barbie had dazzling blonde hair, their eyes shimmering like pearls beneath thick lashes. Their lips were cherry-pink or apple-red, with bright smiles. But what captivated me most were their clothes: a sky-blue satin gown, a daffodil-yellow tulle dress, a pink mini skirt, cute tops, denim jeans… plus crystal heels, sparkly earrings, fashion handbags. It was a world of magic.

In our village, no one owned such toys. They belonged to television commercials, never to girls like me.

Fen and I dressed them up for shopping, for balls, for daydreamed adventures. I lost myself in the moment — but deep down, I knew I couldn’t stay long. Still, I wanted to touch that satin dress one more time. As if I held it just a bit longer, I could remember it forever.

As I left Fen’s house and reached the corner of Pingde Road, I saw her — my mother — already waiting, storming toward me, a bamboo cane in hand.

“Where’d you go, huh? Where?! And now you remember to come home?” she shouted, hitting me as she yelled.

Under the gaze of neighbors, she whipped me all the way home. I kept my eyes on the cloud, not crying, not begging — only my eyes rimmed red, like Barbie’s cherry-pink lips.

Back home, no one cared to speak to me. I quietly took a bucket and filled it with hot water from a stove, a large clay-and-brick hearth where we fed bamboo sticks and bundles of firewood to heat water.

I carried the heavy bucket, arms straining, burning steam rising against my face. I set it down in the bathroom, mixed it with some cold water, and sat on a low stool. My feet soaked inside the bucket, arms wrapped around my legs, chin resting on my knees. I stared blankly into the steam from the bucket. Warm mist touched my cheeks, and then — tears, falling straight into the bucket.

Were they meant for my welted and bruised legs?

A child’s tears are a plea for warmth. And when warmth doesn’t come, the tears stay hidden. Maybe it was the steam, gentle and kind, that drew mine out.

I dipped a towel into the warm water and draped it over my shoulders, hoping my body could feel even a sliver of that warmth

The price of indulgence was pain — I had tasted it.

Barbies were beautiful — I had to part with them.

My fleeting childhood — so short —

it already slipped into yesterday.

The thought alone made tears well up again. I buried my face into my knees so the tears would not roll across my cheeks, but fall straight into the bucket instead, asking nothing, claiming nothing.

I dried the tears from my eyes, wiped the water from my body. Got dressed and left the bathroom. Back in the bedroom, I folded the pleated skirt that bore the stripes of the cane and took out the winter uniform pants at the bottom of the clothing box. For the next few weeks, the pants would veil the sorrow that marked my farewell to childhood.

Soul Whisper:

I was just an eight-year-old little girl who touched a piece of beauty and paid the price for it. My childhood didn’t vanish in a single blow. It splintered quietly, across one road, one bamboo cane, one forbidden dream.

Mother’s tenderness lived side by side with her rage. As a child, I never knew which version of her would be waiting for me at the door: a mother who saved coins to buy us noodles, or a mother who broke bamboo sticks against my legs.

But I knew she was never a monster. She believed every coin must be earned with sweat. She found ways to place her parents’ comfort above her own. She was a woman cornered by hunger, her love twisted by poverty into shapes that wounded even they tried to protect.

And so, her hands gave and her hands struck. But I never held resentment against her. Because we were just two souls, bound together in the same darkness, fighting to survive.

She was hunger’s daughter, and I was hers.

Chapter 6 The Flight of a Dream

From the second grade on, peace and quiet officially resigned from my life.

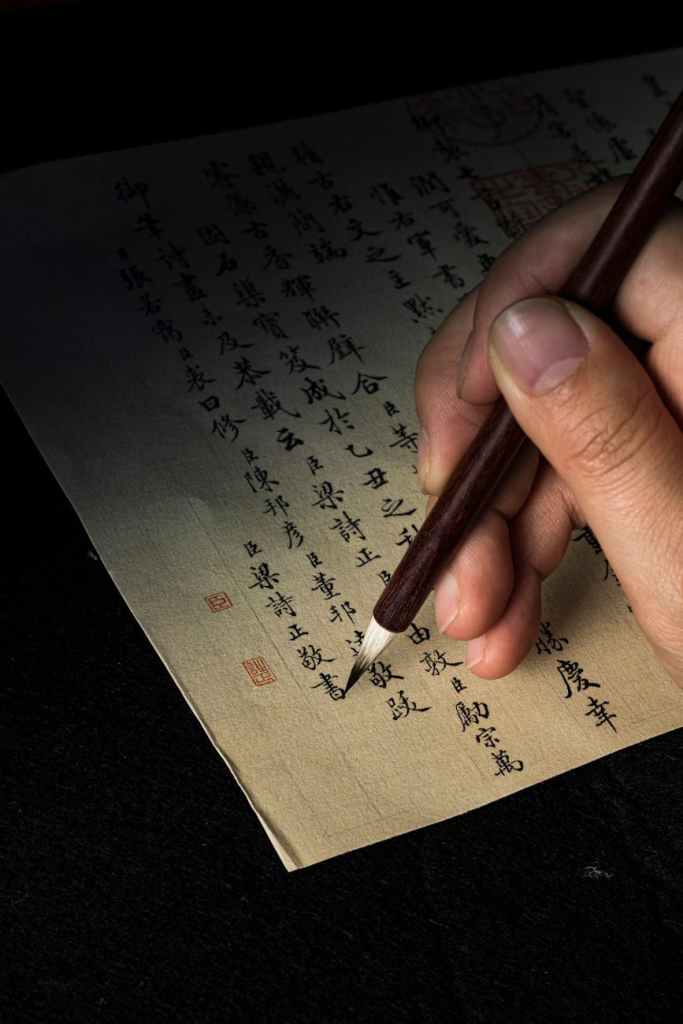

Every term-exam ended with my name at the top, which apparently meant my face had to show up at every possible contest — speech, calligraphy, recitation, dancing, Mother’s Day card design, you name it. Basically, I was the class’s all-purpose representative.

And over time, things began to change. My classmates started electing me to be the class leader. They asked me to help mediate, to assist with their lessons. Their eyes looked at me differently — as if, for the first time, they saw a person instead of a label.

When my third grade teacher, Miss Yu, signed me up for that so-called plein-air watercolor contest, I had no clue what “plein-air” meant. I didn’t even have a set of watercolor paints of my own, nor the brushes.

It wasn’t until I stood at the park where the contest took place, watching other kids set up their easels and unfold shiny watercolor sets, that I finally understood: we were supposed to paint the scenery in front of us.

In my hands were only a few old brushes borrowed from the school’s storage closet. The bristles splayed out like tiny brooms. The paint box was dry and cracked, the colors bleeding together like a spoiled stew. I spread a sheet of paper and copied what the others were doing — dipping in water, mixing colors — like a student sneaking glances at someone else’s test.

Somehow, against all odds, I walked away with second prize of the county-wide contest.

The teachers cheered as if they had raised a hidden genius. But me? I was just confused. My prize wasn’t cupcakes nor a brand new watercolor set. The school rewarded me… the walls.

“Beautify the campus,” the principal announced proudly, “so visitors can see our glory.”

Just like that, I had the outer concrete walls of the entire school to showcase my artwork.

So there I was — sweating under the sun, painting the walls like a miniature construction worker. Glory had painted me right out of classroom, and onto a wall that was never going to take an exam for me.

At school, I kept being pushed onto stages I didn’t even know the names of. To others, I looked like this wonder kid always soaring ahead. But to myself, I was just a little girl, running breathless, never truly knowing where all this flying was taking me.

The walls I painted were wide, but they never opened into a future I longed for. My dream came from somewhere else entirely…

I don’t remember when it started — only that whenever I caught sight of a piano, something in me sparkled like starlight. And whenever I heard its music, the whole world dissolved into a hush. Others spoke of heavenly sounds, but I didn’t need their definition. For me, the piano was like the night sky — its notes, constellations that lit the darkness.

There was this big mansion with beautiful garden in our village, and from its second floor windows often came the beautiful sound of piano. Each time I passed by, I’d stop and listen, utterly mesmerized, picturing myself playing it. But in a household weighed down by poverty and illness, the piano wasn’t just a luxury. It was another world entirely, a star on the sky I was never meant to reach.

Grandfather, nearly eighty, sat in a wheelchair and needed constant care. Mother, illiterate, worked long hours sewing judo and taekwondo kimonos in a garment factory. Her daily wage wasn’t even enough to pay for a single hour of piano lessons. And I — the worthless girl, the child no one believed in. To even imagine touching the keys of a piano was the kind of dream only a fool would dare. But a fool like me still daydreamed about it endlessly.

One day, as we worked side by side at our sewing machines, Mother muttered,

“I wish the Japanese folks would order more large-size kimonos,”

“The large one pays three dollars, and the small one a dollar fifty. But they take the same damn time to sew!”

“Mom," I said, after doing the math in my head.

“I work fifty, maybe sixty hours a week. If I take the pay of thirty hours, I could afford one piano lesson. You could have everything else. And I’ll sew really fast, making as much as I can…. I promise! You won’t even have to check how many I finish each day. Please let me learn piano….."

Maybe she saw how hard I always tried to be good. Maybe she felt sorry that she never offered me anything. Whatever it was, she nodded.

Her nod was hesitant, almost reluctant. But it was enough to set my heart soaring — right out the open window beside the sewing machine, flew over the rice meadows, over the baseball field, and straight to the mountaintops beyond. I couldn’t wait to share my wonderful news to the sun — my only friend for years, who came to me each morning, wrapping me in golden warmth, when no one else did. For the next few days, I finally understood what it meant to smile so wide your cheeks hurt.

Then came the day of my first lesson.

I stepped into the classroom with my heart full of nerves and awe. My teacher, Miss Chen, was graceful and kind — like she had just walked straight out of a storybook.

In the center of the room sat a glossy black piano, so polished it reflected the ceiling lights like still water. The air-conditioner hit me like a sudden cold front. The moment my fingers touched the piano, I almost pulled my hands back.

The keys were colder than I imagined — cold like marble, cold like the nights I spent alone. My hands trembled from more than just the chill. Miss Chen sensed it and gave me a warm smile, and slowly, I began to relax.

Something inside me — something long frozen — began to thaw. Every note I struck was clumsy, almost soundless, yet to me it was thunder. It was as if the piano was whispering: “you’ve found me at last!”

That hour passed in a flash. From then on, I’ve waited each week’s lesson with quiet and burning anticipation. Even the long hours of sewing felt lighter, maybe because my heart was finally smiling.

That impossible dream — that foolish wish — had come true. Not because I believed in miracles but because I refused to accept what others called “impossible”.

I didn’t want to be a “useless mutt” they said I was. So I did everything I could to be useful. When you are useful, you have leverage. Small bits of leverage, added up over time, became bigger bargain power. With years of sewing, I finally earned something I thought I could never have — piano lessons.

However, piano is not a skill one could master overnight. It takes a tremendous amount of time, money, and patience. My dream had taken flight, but how high or how far could it actually soar?

Soul Whisper:

There was a time I thought the piano belonged to another world. In my world, hands were for sewing, not sonatas. But somewhere between the hum of the sewing machine and the rustle of rice fields outside, a question bloomed quietly in me: what if I asked?

When I finally did, it wasn’t with loud hope, but with careful calculation. It didn’t erase the hardship. I still sewed, still worried about money, still carried the label of “worthless girl.” But each week, for one hour, I crossed into a different world — the one I used to only hear from afar. A world where my hands made music. A world where something in me softened and dared to believe.

The truth is, I don’t know how far that dream will take me. But I know what it gave me: proof that even in a life stitched with silence and survival, a dream — just one — can lift the soul high enough to keep going.

My hands, once chained to thread and cloth, had touched keys that unlocked another world.

Chapter 7 The Tortoise and the Hare

During our story class, Miss Yu told us the story of “The Tortoise and the Hare.”

As soon as she finished, I shook my head in disbelief and said “Impossible!!”

Miss Yu looked at me, puzzled. She didn’t understand why I was so against it.

“I just don’t get it! Why would anyone force a tortoise to race in the first place?”

It wasn’t that I didn’t want to believe the tortoise could win. It was just … I was the tortoise. And winning was never something written into the script of my life.

“But the tortoise did win!” my teacher and classmates all chimed in.

Fables are innocent. Reality isn’t.

Yesterday’s hare lost because it napped. But today’s runs on Energizer batteries, and tomorrow’s will be faster still. Even if I won today, could I win tomorrow?

I looked around in the classroom, all of them hares unable to understand the shadow that lives in a tortoise’s mind. A hare can run if it wants to. Jump, leap, sprint. But a tortoise? It carries a heavy shell and walks on short legs — what speed could it possibly have? A tortoise racing a hare is like asking a crocodile to climb trees against a monkey. Life is a marathon that lasts decades — how could the tortoise ever win?

I was the tortoise on life’s track. If I wanted a chicken leg, I had to beg leftovers every day. If I wanted a piano lesson, I had to trade 30 hours of labor just for one hour of music. So how, exactly, was I supposed to run this race?

That question rooted itself inside me. It knotted up my soul. I kept asking: How does the tortoise win?

When I finally began piano lessons, we didn’t have a piano at home. My classmate Ling, the daughter of a grocery store owner, had been playing since she was three. She’d been running this race for seven years already. And me, this little tortoise, hadn’t even found the starting line. That gap made my heart sink.

Tortoises have no special talent. If they want to race, they can only walk — one slow step at a time. So I told myself: I can’t afford to let discouragement weigh me down. I had to focus on the finish line.

I took calendar papers and drew black-and-white keyboard to create a paper piano. Every free moment, though not much, I pulled it out and practiced — training my fingers to remember the position of each key. The keyboard couldn’t sing, so I imagined the sounds in my head.

Every time my fingers moved, I told myself: I can have a voice too. I memorized the teacher’s techniques and practiced them on my thighs while walking or riding the bus — pressing, flexing, strengthening my fingers through thin air.

Eventually, I came to a new understanding of that fable. The tortoise’s opponent was never the hare. The real opponent was its own body — its heavy shell, its short legs. To win the race, the tortoise had to defeat the limits it was born with.

At the age of eleven, I made a vow to myself. I would race against the person I was yesterday. I didn’t need to care how fast the hares were or how many advantages they had. I would focus on my own rhythm. As long as each step I took was steadier than the last, longer than the one before, I was winning.

Two years later, Ling and I sat for the same level of piano certification. Mother and I had finally saved up enough to buy a cheap off-brand piano. But to me, it was my very own Steinway.

Soul Whisper:

I was never asked if I wanted to race. I was simply placed at the starting line, with a shell on my back and no map in hand. The world clapped for the hares, sleek and shining with head starts and confidence, while I — the slow one — was expected to keep up or be forgotten.

But I kept walking.

When others had keys, I drew my own. When others had melodies, I imagined mine. While the world sprinted, I studied the ground beneath my feet — measured each crack, each stumble, each breath. I turned my body into an instrument. My fingers became memory. My back carried both hunger and music.

No one saw the race I was in —

not against the hares, but against despair.

Not for applause, but for becoming.

Every step I took was a vow:

I will not be fast, but I will be true.

I will not arrive early, but I will arrive whole.

My voice may be quiet, but it will echo with soul.

And in this long race called life, the tortoise is not slow —

She is steady.

She is sovereign.

She is still moving.

Chapter 8 When Darkness Arrived

“Please, miss… your factory is so big, there must be something I can do — anything. Just give me a chance,” my mother said, her voice low and rough.

“I’ll work hard, I swear. You don’t even have to pay much.”

She wasn’t used to beg. But that day, she was ready to crawl if that’s what it took to feed us.

It was 1990. Suzuki Motor had partnered with Taiwan’s Tailing Industrial Company to begin exclusive production. The new factory was built right behind our house, a monumental event in our little village — hundreds of workers needed, enough jobs to support several surrounding communities. My mother wanted to apply. But without any education, she was turned away at the gate.

“If you don’t have any degree, the only position available is as a janitor. Do you want it?” the HR woman said.

“Please, let me come in before 8 and after 5. I already got a job at the garment factory. I need both to get by!” my mother asked cautiously.

“That works perfectly. You won’t interfere with the workers. Come try it for a month. Let’s see if it’s a fit.”

And so, my mother was given a trial as a janitor. By August, we officially became Suzuki’s janitorial staff. And I — 11 years old — entered the darkest days of my life.

I call it my season of darkness because it marked the beginning of my second full-time job as a child labourer. My sewing job — stitching judo kimonos — became part-time. My identity as a student was hanging by a thread.

What haunted me most were the 4AM wake-ups. At an age when children cling to their sleep like bears, my body had already become a puppet — stumbling through the cold, barely attached to consciousness. My senses didn’t fully return to me until we passed the graveyard.

When Suzuki built its factory, it bought up most of the land — except for a small plot owned by the Sung family on the east side. That plot had several graves, which remained untouched.

Every morning, my mother and I had to bike through a densely wooded narrow path skirting the factory wall, through tall silver-grass and eerie fog, into the chill of the predawn. The fog made no distinction between the living and the dead. Everything felt alive and haunted at once. My skin bristled. My sleepy mind would immediately begin chanting: “Merciful God, protect me.”

Every morning, I would clock out at 7AM from the morning shift, rush home for a quick breakfast, then I’d run to school.

That semester, our homeroom teacher, Mr. Yeh, was a man with no passion for teaching. He discovered a genius way to lighten his workload: outsourcing his job to an eleven-year-old. He often skipped class entirely, leaving me — the class leader — to keep the zoo in order and explain the homework. Eventually, classmates started begging me to teach them. So my “teaching career” began with Chinese literature and math.

Standing in front of blackboard didn’t scare me. I could read the textbook once, and the idea stuck well enough to repeat it out loud. The problem was, Mr. Yeh decided to make it a permanent arrangement. He kept handing me his chalk, his red pen, then even the grading sheets. By the end of the term, I was essentially an eleven-year-old civil servant — but without salary, benefits, or a union.

Yet miracles didn’t happen. Despite my unpaid labor, our class’s midterm and final scores were always the lowest in the grade. How could they not be? I was just a kid myself and a poor one — I had no other resources except the textbooks.

In Taiwan, families with money sent their kids to cram schools, stacked their desks with practice booklets, and timed them with mock exams. I had none of that. If life had been fair, I would have had a math tutor. Instead, I was the math tutor for all my classmates.

Even if I had been handed extra reference books to help out with my study, I wouldn’t have had time to open them. My study time was the ten minutes of recess between classes, while other kids played dodgeball or jump-rope. I squeezed one minute into two, scribbling homework before the next bell rang.

After school, I sewed kimonos to pay for piano lessons, watered crops we hoped to sell, then reported to Suzuki factory for night shift until 10PM. Then at 4AM, it started all over again.

I was like a spinning top powered by other people’s negligence, whirling until I forgot what rest even meant. Exhaustion felt like a rocket propelling me straight to Mars.

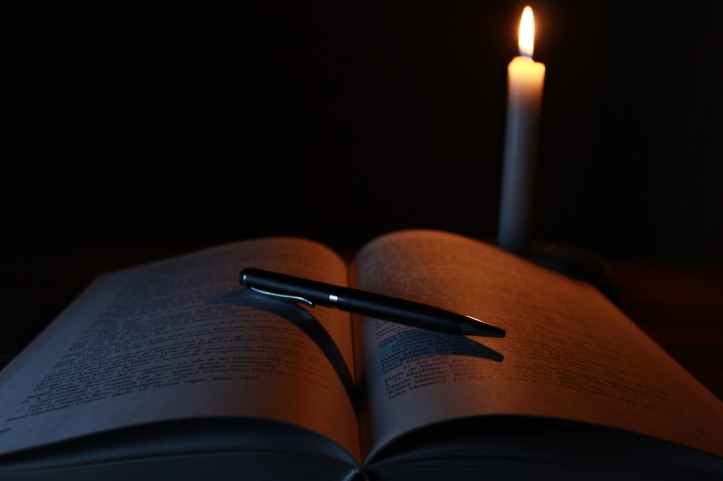

And in the middle of all that darkness, piano became my lifeline. That one hour a week — my piano lesson — was the only thing keeping me from drowning. It was my piece of driftwood in a merciless ocean. I clung to it like it was all I had. Because… it was.

There was no light yet. No sign of dawn. And then — one race dragged me straight into the eighteenth circle of hell — just when I thought it couldn’t get any worse.

Soul Whisper :

Some children are born to chase butterflies. I was born to scrub factory floors before sunrise, to rise before the stars disappeared, to pedal through fog and ghosts and graveyards. My education began not with books, but with bleach, with hunger, with my mother’s sacrifices echoing in my body.

And yet — what saved me was not strength. It was music. Not the triumphant kind, but the trembling kind, the fragile notes that whispered, “You’re still alive.”

One hour a week at the piano was all I had. It reminded me that even in the graveyard of my childhood, there was still a pulse. And where there is breath, there is still a soul. And where there is a soul, there is still a song.

Chapter 9 The Beginning of One Thousand Dark Nights

Two months from graduation, elementary school was slipping away, but I had no idea the worst was just about to begin.

For our final P.E. evaluation, we had to run a timed 200-meter sprint. Mr. Yeh took us to the backfield track.

In the center of the backfield was a patch of grass, surrounded by eight laps of red clay. I never liked running there. I liked my shoes clean, and the red dust always stuck to the fabric like an insult — dirtying my shoes, staining my socks. But it was P.E. exam, like it or not, I had to run.

As I watched group after group take off, my heart began warming up in my chest. When it was our turn, I lined up in the middle lane — Zhen on my left, Ling on my right. We crouched together at the start line.

The whistle blew. Like stones flung from a slingshot, we launched forward. There’s no such thing as “let others go first” on a track — everyone was running for their lives.

“Only 50 meters left," I told myself. I pushed harder.

Suddenly, footsteps rushed up behind me. I felt a sharp hit on my back. My balance broke. My stride faltered. The red clay came up fast — too fast — then everything went black.

In the darkness, I felt myself being lifted. A searing heat spread from my elbow and knees. But the pain in my right shoulder was like a siren — it howled. I screamed. My mind came rushing back to the world.

I looked at my right shoulder — it was misshapen, bulging out at a strange, ugly angle. Waves of pain slammed through it, again and again. I didn’t want to cry, but the tears came on their own. Blood from my elbow and knees had already soaked into the clay, mixing into clumps of mud that stuck to my legs.

I couldn’t even feel the pain in my hands and knees anymore. My shoulder hurt so much, it drowned out everything else. But the stains — those stayed. Deep red marks on my shoes and socks, marks that wouldn’t wash out.

My right collarbone had snapped, the bone overlapping itself. At the emergency room in Taoyuan Hospital, the doctors forcibly pulled it apart. I had no tears left. No voice to scream. I gritted my teeth, my brows clenched tight in pain. The fracture was so bad, they could only separate it slightly before strapping on a giant shoulder brace.

After the treatment, Mr. Yeh drove me home.

He was a tall, broad-shouldered man, his presence filling the small hospital hallway. In class, he had always towered above us, a little intimidating, his voice more bark than warmth. But that afternoon, I sat in the passenger seat of his sedan, shoulder strapped, body aching, staring out at the blurred lights of Taoyuan city. Silence stretched between us, only broken by the hum of the engine.

When we finally pulled into my village and stopped in front of our house, I caught the flicker in his eyes. He probably had never expected to see poverty like this.

Our roof sagged, patched with corrugated tiles that let in as much rain as they kept out. Whenever a storm came, water dripped everywhere. So Mother had tacked giant plastic bags to the ceiling, fastening their mouths to the walls so that rainwater could slide down like makeshift gutters. It was our poor man’s plumbing system.

When Mr. Yeh stepped inside, his tall frame had to bend low, or else the dangling plastic bags would brush his head. His eyes darted from bag to bag, following the path of rain stains on the walls, to the cracked cement floor where water stains still lingered. His face froze into a look I had never seen before — disbelief mixed with something heavier.

For the first time, perhaps, he saw me not as his “responsible class leader,” not the girl he left in charge when he didn’t feel like teaching, but as a child who lived in a house that barely kept the rain out.

I wondered if guilt crossed his mind — that he had piled so many duties onto the smallest shoulders in his classroom.

He didn’t say anything. But the silence between us felt louder than any lecture. And for the next few months, I went nowhere without that brace.

After only a few days of rest, I returned to my janitorial job. If I didn’t, we might lose the income. My sewing work over summer break suffered — the right arm couldn’t function, and I was slow. Junior high was about to begin. Heavier study. Longer hours. Would life get harder? I didn’t dare imagine.

I kept scrubbing floors with one arm. Kept sewing. I clenched my jaw and worked through the pain. I didn’t dare cry out, didn’t dare show how weak my right arm had become. I was terrified it would be used as a reason to take away the one thing that mattered most to me — piano.

I had fought hard to get on the track, to run alongside the hares. I didn’t want to stop now. Even if I was now a limping tortoise, I still wanted to stay in the race. For piano. For the self I longed to become. I held on. I didn’t let go. Not even when the storm rose.

The sea was roaring, fierce and wide,

My left hand — all I had — held tight.

Still fighting through that endless night,

Clinging to my driftwood with all my might.

I didn’t know how long I’d last,

But still held hope I wouldn’t be cast —

That storms turn to morning dew

Beneath a sky of blue.

May I feel the warmth of sunlight

Through the ache of every trial,

May I rise, and grow with every mile.

Soul Whisper :

Some pain is sharp, like bone breaking against clay. But some pain is quiet — long, flat, and wide like an ocean. That summer, I tasted both.

When the whistle blew, I wasn’t chasing victory. I was chasing dignity. I was chasing the part of me that still believed I could run with the hares. But the ground met me faster than hope, and from that moment on, I learned what it meant to fall and still keep moving.

My collarbone split, and with it, the illusion that effort could ever protect me. But I still showed up. I still worked. I scrubbed factory floors with a strapped shoulder and silent tears. I feared more than the pain — I feared losing piano, the only place I felt alive.

So I trained my left hand to hold the world. I clenched my teeth and told no one how much it hurt. Not because I was brave, but because I was afraid the world would forget me if I stopped.

I held on to rhythm like a drowning child holds driftwood. That music wasn’t just sound — it was survival.

In the dark, I told myself: If this is what it means to live, then let me live with all I have left.

Let me rise, even if bent.

Let me grow, even if slow.

Let me keep playing, even if with one hand.

Because even the smallest melody,

when played with hope, can call the dawn.

The clay that bloodied my knees became the ground I rose from. Even in one thousand dark nights, I would not stop moving.

Chapter 10 Breaking Through the Siege

When I entered the middle school, I could immediately feel a shift in the classroom atmosphere.

In elementary school, my class was more like a field of wild grass than a garden — no fences, no pruning, just left to grow whichever way we pleased. Our teachers often didn’t show up, and no one seemed to mind. Learning was optional. Structure was absent.

Somehow, amid the chaos, I became the unofficial teacher, explaining math problems, walking the classmates through Chinese literature lessons or science experiments. I didn’t think of it as special — just what felt needed to be done: helping my classmates out.

Naturally, I was top of the class for every term exam. By the time we graduated, the County Mayor’s Award, given to the highest-achieving student, landed on my lap. Not because anyone planned it that way, but because no one else had been watching closely enough to stop it.

Middle school was an entirely different universe.

There were fourteen classes in my grade, and each class had more than fifty students. I’d been placed in Class 102 — a room packed with the County Mayor’s Award winners. But unlike my laid-back elementary school days, this new class buzzed with a kind of academic electricity I had never encountered.

Hands shot up before the teacher even finished a question. Students practically raced each other to the answer. Within weeks, all the star students had already been assigned as “subject leaders” — little lieutenants for each subject, commanding mini empires of knowledge. Compared to the sleepy field I came from, this was a battlefield.

The teachers, too, were a world apart. In elementary school, they followed more of a Taoist philosophy: hands-off, no demands, no punishments. We were left to grow wild, like plants in an open field. But in middle school, it was all Legalism — strict discipline, zero tolerance. Every missed assignment, every failed evaluation, was met with a swift swing of a bamboo cane. The academic pressure didn’t just rise — it multiplied!

The classroom now was no longer a place of learning — it was battleground, and every exam was a bloodbath.

As if things weren’t hard enough, I barely had time to study. My early mornings and nights were packed with work. While my classmates biked to cram schools after class, I biked to Suzuki factory. My broken collarbone never had a chance to heal. Months had passed since the injury, but the pain lingered, dull and stubborn, flaring up whenever the wind blew or the rain came.

Rainy mornings in winter were the hardest. While others were still in bed, I’d be out for the morning shift in the bitter cold. My right shoulder aching with every step. Cold rain hitting my face like slaps and warm tears mixing in with the chill. It was the sound of my body and soul, crying out together.

But I knew one thing for sure: in this new environment, I had to prove myself. I had to rise to the top, not for the pride but for survival. Only by standing out could I beg for leftovers from the classmates — doing my job as a good guard dog. If I didn’t, I’d become a joke. And every day at school would be another kind of punishment. So I traded the only resource I had left — sleep — for a fragile thread of dignity.

After the night shift from the factory, I would stay up alone past 10PM, studying under a dim light, wrestling with exhaustion. But the results were limited. Waking up before 4AM for physical labor left my body drained. Past midnight, the words on the page blurred into dancing shadows and sometimes I jolted awake with the pen still in my hand. I had to pinch myself just to stay awake. Still, it never lasted long. Four hours a day of sleep wasn’t nearly enough. My body was fraying at the edges, like a lamp running out of oil. I had to find another way.

Eventually, I devised a survival hack: squeezing brilliance out of crumbs of time.

I made flashcards during class — filled with English vocabulary, Chinese poems, or textbook passages. These cards became my secret companions, tucked into my pockets as I swept the floors, scrubbed the toilets, and walking to school.

Whenever my body was busy but my mind free, I’d pull out a card and recite. Those were the moments when ancient voices kept me company: Tao Yuanming with his quiet wisdom, Li Bai and Du Fu drifting through the air like echoes from the golden age of poetry.

拖把拖曳著「兒時記趣」,

掃把輕輕理出「桂花雨」。

在「陋室銘」中刷東圊,

在辦公桌上拭「夏夜」。

我揮手窗櫺,

便再別了「康橋」下的波光艷影。

My mop would hum with memories of childhood essays, my broom would trace the outlines of autumn rains. As I wiped desks and windows, I whispered farewell to the imagined river under moonlit bridges.

Learning slipped in between labor, gently and persistently — like sunlight threading its way through dust.

Months later, in a class full of overachievers, I somehow broke through the siege. I clawed my way back to the top. With that, my “leftover-collecting business” resumed in full force.

In this brutal middle school survival game, I learned a truth that stayed with me for life: Survival is not just about working hard. It is about breaking through the siege — with strategy, with courage, with an unyielding will to keep moving.

Soul Whisper:

I wasn’t the brightest, the strongest, or the most prepared. I was just a girl with tired hands and a stubborn mind, gathering knowledge from the cracks of each day.

Some grow under sunlight. I grew under pressure — between labor and silence, between pain and hunger. I didn’t study to prove I was better. I studied because I couldn’t afford to fail.

If life wouldn’t give me space, I carved it from scraps. If no one expected anything of me, I chose to expect something of myself. I wanted to find my own way through the maze, carrying a light in my heart! So I kept walking and will keep walking.

Chapter 11 Grandma’s Loving Lunchbox

I parked my bicycle by the front door and glanced at my watch — 6:10AM. Ten minutes late again. My breath steamed in the winter air.

The winter solstice had passed. The wind was stronger today, and the fallen leaves — more than usual — took longer to sweep from the stairs. It looked like, for the next month or two, I’d have to leave 15 minutes earlier. Out the door by 4AM.

I stepped into the kitchen. On the table: sweet potato porridge, a few pickled vegetables, fermented tofu, and marinated clams — Grandma’s specialty — salty and savory, they paired perfectly with the porridge. My stomach had been growling long before I walked in.

“Granny, I’m back. I’m starving."

By the corner of the dining table sat a metal lunch box. Inside: a soy-braised chicken thigh, a slice of omelet, and stir-fried cabbage. It looked delicious.

I glanced at my watch again — 6:15. No more dawdling! If I didn’t leave home by 6:30, there was no way I’d make it to school by 7AM. And that meant one thing: squat punishment — a full-on workout for my thighs.

I quickly scooped a bowl of porridge and set it on the table to cool down. Then, sprinted to my room — changed into my school uniform in two minutes, grabbed my backpack, and dashed back to the kitchen. I passed by my brother’s bedroom. He was still in bed, warm under his blanket.

Back at the table, I didn’t have time to care if the porridge was still hot. I picked up the bowl and poured half of it straight into my mouth. Then hurriedly grabbed a small pot, filled it with water, set it on the gas stove, and turned on the flame.

I returned to the table, grabbed a few slices of pickled vegetables, and poured another half bowl of porridge into my mouth. I didn’t even feel the heat anymore — there was no time to feel anything and I had to hurry. Then I rushed to the fridge — took out an egg, a handful of baby bok choy, and a stalk of celery. Washed, chopped, tossed them into the pot.

Back at the table, I scooped another bowl of porridge, picked up a piece of fermented tofu, mashed it into the porridge, and slurped it all down to my stomach.

I walked quickly to the cupboard, grabbed my lunch box, filled the box with a layer of rice, and set it back on the table. Then I returned to the stove. Bok choy was boiling furiously. I tossed in a big pinch of salt, beat the egg and poured it into the pot — then turned off the heat.

Finally, I drained the soup, tipped the cooked bok choy and egg into the lunch box, added a few slices of pickled veggies, and snapped the lid shut. Breakfast eaten, lunch box made, school-bound. All in under fifteen minutes!

“Granny, I’m off to school!" I called out before heading out the door.

This kind of military-style morning routine was just another day in my middle school life. As for Grandma’s loving lunches — they were a kindness I never got to enjoy.

Grandma, as I remember her, lived without much display of joy or anger — just quietly going about her days, faithfully preparing three meals and taking care of Grandpa, who had been in a wheelchair for years. The only person who ever seemed to spark real joy in her was my older brother.

Both Grandpa and Grandma were born before World War II, during the Japanese colonization, when they were considered second-class citizens. They lived through war, through the retreat of the Chinese government to Taiwan. Two small lives caught in the undercurrent of history. Nothing came easy. Everything had to be clawed from the edge of survival.

They had given birth to eight children. The children came in haste, only to return, one after another, to dust — no names engraved. No trace of their lives was kept. Only my mother survived. And so, I came into their world still echoing with ghosts they dared not name.

The grief of losing children — at first, perhaps, it shattered the heart. But over time, as the wound healed and tore, again and again, the heart could only sever feeling from itself, until it learned to beat — numb, and without memory of pain.

I saw, in the dryness of her eyes and the deep furrows time had left on her face, the buried sorrow she never spoke of. Perhaps the quiet wound she carried all her life was not having a son to continue the family line.

In rural Taiwan, daughters were often considered “spilled water” — destined to marry out, to belong to another household. To my grandparents, I was the “money-waster” — another mouth to feed, the expendable one. To them, only a boy could keep the family rooted.

After my brother was born, he became the center of Grandma’s world. She raised and cared for him as if he were her own son.

When Brother started kindergarten, Grandma would walk half an hour each day to the school and linger outside the fence, peeking through to make sure the teachers fed him. If he scraped a knee or felt the smallest grievance, Grandma would cradle him in her arms, soothing him with secret stashes of candy.

“Don’t you dare hit him!!” she would shout.

Whenever Brother misbehaved and Mother raised a bamboo stick, Grandma would burst out of the kitchen and shield him with her body.

However, she never had financial power of her own. So she gave in the only way she could: by saving the best bits of food for her grandson, offering love in the form of whatever was on the table — the one domain still within her reach. So the best food always ended up in Brother’s lunchbox.

Grandma rarely spoke to me. And when she did, it was to order me around: to follow her to the neighborhood creek to do the laundry, or to wash the dishes after meals. I was not a child to be cherished. I was more like a dog they kept — expected to work, to obey, and to be fed just enough …. to make sure I didn’t die.

Every morning, Brother carried to school a lunchbox heavy with Grandma’s love. I carried mine too — scraped together by my own hands. My lunchbox held rice, boiled greens, and a silence that no one in the house thought strange. In that silence, I learned to swallow hunger — not only of the body, but of the heart.

I was thirteen but I understood their resentment toward me — it came from a place of fear, a need to protect what little they had. The cruelty of poverty lies not only in the lack of resources, but in the absence of choice. Each grain hard-won, every offering weighed — everything had to be reserved for the boy in the family.

I didn’t dwell on how they treated me — or failed to. I didn’t have the heart to hold it against them. They, too, were just trying to survive in a life that had given them so little.

I cannot control how others treat me but I’ve learned to be grateful for what is given. When faced with others’ coldness or inaction, I must try to understand and turn inward to ask what I can do instead.

That understanding shaped the way I carried myself in the world: never take anyone’s kindness for granted.

Soul Whisper:

Grandma was an extraordinarily hardworking woman. Except the hours she spent eating and sleeping, she was always working — doing housework, hand-stitching garments, or collecting scraps to sell.

Her coldness toward me was never deliberate cruelty. She was a woman without any education, someone who had spent her entire life toiling with quiet diligence, surviving within the narrow framework handed down to her. She had never been taught to question, never been shown that other possibilities could exist.

In her world, girls were not seen as equals, let alone as treasures to be nurtured. A girl was a family’s appendage, destined to leave, a shadow that barely counted as a “person.” In that patriarchal generation, kindness toward daughters was not just absent — it was unthinkable. So no one wasted tenderness on girls, no one thought to invest love where it was never meant to remain.

In a house where even grains of rice had to be counted, I was the girl who learned to swallow her tears in silence. But even if no one saw my worth, I vowed to become someone of value. No blame, no bitterness — only a quiet question I asked myself every day: What can I do with what I have?

So I swept leaves before dawn, stitched garments with tired hands, and filled the empty spaces where love should’ve been — with usefulness, with effort, with light. I never expected life to give me anything. But deep down, I held onto a fragile wish that one day, even in Grandma’s eyes, I might become more than just a burden.

So I chose to believe this: if I could live with grace and warmth, life would slowly turn its face toward me.

Chapter 12 The Crimson-Stained Keys

“What kind of mess is that jacket!? Zip it up! All the way!”

“Go stand in the hallway!”

My homeroom teacher’s voice lashed out, eyes fixed on my uniform jacket.

The zipper of my school jacket hung half-open. The right collar drooped lazily over the edge of my shoulder. It looked less like a student’s uniform and more like a fur stole draped over the arm of a socialite. That jacket wore me like a woman revealing a bare shoulder — coquettish, though unaware.

I didn’t say a word. Just zipped the jacket up to my chin, the collar pressing awkwardly against my throat. The teacher’s command was like an imperial decree — never to be questioned. Silently, I stepped out of the classroom. A chill drifted in with the late autumn breeze, and a sting rose quietly behind my eyes, blurring the falling leaves outside into a watercolor of sorrow.

我不敢吭聲,

默默地拉上外套拉鍊,

領子頂到了下巴,

右肩頓感不適。

師命如君令,不可違抗,

我安靜地步出了教室。

秋風吹來,一陣涼意,

眼裏浮上一陣酸楚,

模糊了廊外的片片秋意。

If I could, I too would’ve wrapped my shoulders warm, shielding myself from the wind. Who was I to pretend?! A girl who lived on leftovers, playing dress-up in scraps of pride? Wasn’t that just asking to be mocked?

Ever since my collarbone fracture, it had gone from bad to worse — until even the weight of a jacket became too much to bear. Writing with my right hand had become a strain. On cold days, my jacket ended up draped across me like a socialite’s shawl — worn more for show than warmth.

To save what little strength I had in my right arm for playing the piano, I trained my left hand to take over. Unless a task demanded both hands, the left did it all — brushing teeth, writing homework and evaluation papers, scrubbing toilets, mopping floors. It wasn’t just a hand. It was my quiet partner in survival.

And this poor left hand — after years of scrubbing with harsh detergents — was red, peeling and cracked. When I pressed the piano keys, the skin of the hands would split open and bleed, staining my teacher’s piano with quiet apologies.

如今的鋼琴課,已經是血淚的堆疊。

雙手承著苦痛,延續著一直以來的夢。

染血的琴鍵,繼續奏著未完的心願。

Piano lessons had turned to blood and ache,

My weary hands for a dream at stake.

Crimson-stained keys,

a wish still dares to wake.

What is it that keeps me going? I asked myself.

School was a regime of ruthless control. In the name of ‘teaching by aptitude,’ the teachers set my passing bar to ninety out of a hundred. Falling short meant a whipping with a bamboo stick, then kneeling in shame in front of the statue of Chiang Kai-shek at the school gate. The weight of schoolwork bore down like a silent avalanche — suffocating and relentless.

Because my mother had fallen ill, the cleaning shifts stretched longer — twice the hours, twice the weight. By the time I got home every day, it was almost midnight. Homework piled like a mountain. Tomorrow’s exams? Not even a glance. Only the desk lamp stood by me — my lone companion in this quiet war.

My body, day after day, fed on the clumsy lunches I threw together. The leftovers too old that food had already turned sour. Hunger left no room for hesitation so I swallowed whatever I had, even when my stomach protested with waves of nausea or head spins. My body begged me to stop — aching, dizzy, on the edge of collapse. But I was a stubborn general, still hell-bent on conquering every fortress ahead.

What was holding me up? I asked myself. Maybe it was defiance.

I refused to live a life of humiliation. Refused to be a dog they thought I am. Knowledge burnt away my shame. Music lifted my soul above the dirt. The sharp-edged, quiet fire in the chest — that’s why I couldn’t give up. I had to rise. I had to break free.

Standing alone in the hallway outside the classroom, only I knew what I was holding on to. No one understood the pursuit clenched in my hands. They didn’t get it — why I kept going when it hurt so much. Why I did not stop to rest when I was tired. My brother didn’t understand. My mother didn’t understand, nor did my piano teacher. But I did, and that was enough.

I spoke to my own body:

I know you are hurting —

but please ... hold on a little longer for me.

I can’t promise you a future,

For the future is still clouded and unknown.

Years of war, drums of strife —

I shall not rest before my mission breathes life.

Time marches on, my body worn thin,

But as long as strength remains within,

Crimson-stained keys shall strike the strings still.

As long as I stand,

this “lone horse on an ancient road”

Shall unfold beneath the solitary lamp’s chill.

我對著自己的身體喊話:

我知道你們痛,但請再為我堅持。

我無法承諾未來,因未來仍混屯不明。

烽火連年,戰鼓不息,

出師未捷,誓不休棄。

時間步步逼迫,身心皆已疲憊。

但只要還有力氣,

染紅的琴鍵,將繼續敲打鋼製的琴弦。

只要身體沒有倒下,

「古道西風瘦馬」,將繼續攤展在孤燈下。

Soul Whisper :

I was never the girl meant to be seen. Not in that jacket, not in that hallway, not in that life. But I kept standing. Every time I zipped up that jacket, tightened my jaw and stepped outside the classroom, I was telling the world — I’m still here.

The piano keys never ask for perfect hands. They only asked for presence. So I gave them everything I had — cracked and bleeding hands, even when I had no sleep, even when the world around me said I shouldn’t bother.

What held me up wasn’t glory. It wasn’t praise. It was something quieter: a promise I made to myself, with an empty stomach and trembling legs — that I would not disappear.

People saw a stubborn girl, maybe a strange one. But they didn’t see what I was protecting: my right to dream, my right to rise, even with broken wings.

I didn’t know where the road would lead. But I knew this: As long as my fingers could press a key, as long as breath stayed in my chest, I would keep walking. Even if no one clapped. Even if no one understood.

Because somewhere deep down, a quiet voice whispered:

You are not nothing.

You are becoming.

Chapter 13 Hard Is The Journey

“You got the top score of the whole school!!” A few classmates rushed over to my desk, faces lit up with excitement.

“Really?!” I asked, half happy, half in disbelief. It felt surreal.

It was the second semester of the second year of middle school. The school had organized a mock exam for students preparing for the high school entrance exam.

In Taiwan of the 90s, school wasn’t just school — it was a giant pressure cooker with the lid sealed tight. Everything revolved around the exam. Not “an” exam. The Exam.

We called it the High School Entrance Exam, but it might as well have been called the Hunger Games. One score decided our fate: which high school we entered, which university we could dream of, which jobs might someday take us seriously.

And this exam wasn’t just a test — it was a national sport, demanding everything.

We had to know by heart three years of material from every subject — Chinese, English, Math, Physics and Chemistry, History, Geography, Biology — all packed into a single weekend. It was like cramming the entire Library of Congress into our head, then being asked to restate the exact page numbers on command.